Currently one of the main buzz topics and research areas in sports is concussions – diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. But researchers are finding that repeated blows to the head, even without the presence of a “concussion” can be even much more substantial and devastating. CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy, is a progressive neurodegenerative brain disease found in people with repetitive brain trauma. At this time, CTE, can only be officially diagnosed postmortem through autopsy, however, new research within the past 2 years, may be able to identify this tragic disease process while the patient is experiencing the symptoms as well as be an indicator of the disease.

In CTE, a protein called Tau forms clumps that spread across the brain, killing brain cells. Initially the frontal cortex is affected by these clumps of protein. Early symptoms that may be seen include changes in mood and behavior, problems with impulse control, aggression, depression, and paranoia. As CTE progresses, there may be marked atrophy of the hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum. Symptoms of this level of brain involvement may include, progressive muscle weakness, gait and balance disturbances, and worsening memory and cognitive function.

CTE is currently being studied and found amongst athletes, military service men and women, and others with repetitive brain trauma. The most common sports to have repetitive head injuries include boxing, football, hockey, and soccer. In 2008 the CSTE (Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy) at Boston University school of Medicine started the CSTE brain bank at the Bedford VA hospital to analyze the effects of CTE. As of 2016, they have confirmed diagnosis of CTE in 96{3f67d5d22d5361fa72c7bd5e8e18baf70d398a2d581c9e99367caf83f4ceb942} (90 out of 94) former NFL players that were analyzed in postmortem brain studies”. Overall, the number is staggering! Former Cincinnati Bengals player, Chris Henry, was one of the 90 individuals with confirmed CTE during autopsy. The researchers are finding that it’s not just about making “better helmets” because the brain still ricochets within the skull causing injury. The NFL is using this information to make rule changes that will promote player safety. In March of this year, a new rule will penalize players for lowering their helmet to hit another player. Hopefully, the sports community will continue working with healthcare researchers to understand the potential dangers, and to embrace player safety above all else.

Unlike the head injuries that occur in most sporting events, recent military head injuries are the result of blast wave exposures. The blast injuries are thought to cause a severe “whiplash” injury inside the skull, mirroring the effects of a sub-concussive force on the brain. “Nearly 20{3f67d5d22d5361fa72c7bd5e8e18baf70d398a2d581c9e99367caf83f4ceb942} of the more than 2.5 million U.S. Services Members deployed since 2003 have sustained at least one traumatic blast” according to Warden, D in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. Dr. Anne McKee, one of the primary neuropathologists at the Boston University CTE brain bank, found that of the 102 brains of military service men that were examined, 66 showed signs of CTE.

With many people that have these “blows” to the head, they initially appear fine returning to the playing field and battle field without symptoms. Dr. Ann McKee refers to it as an “invisible injury”. These delayed outward symptoms are partially why CTE is difficult to identify and differentiate it from other conditions, as well as this may be the reason the injury to the head continues to occur because it’s not initially seen. However, what is being found at the CTE research center, is that the brain is not the same even seconds after the injury. Also if there is a subsequent exposure, the rate of injury could be greatly accelerated. Dr. Goldstein, from the team at the CTE brain bank, predicts that “this is a disease and problem that we are going to be dealing with for decades. It’s a huge public health problem…it’s a huge moral responsibility.”

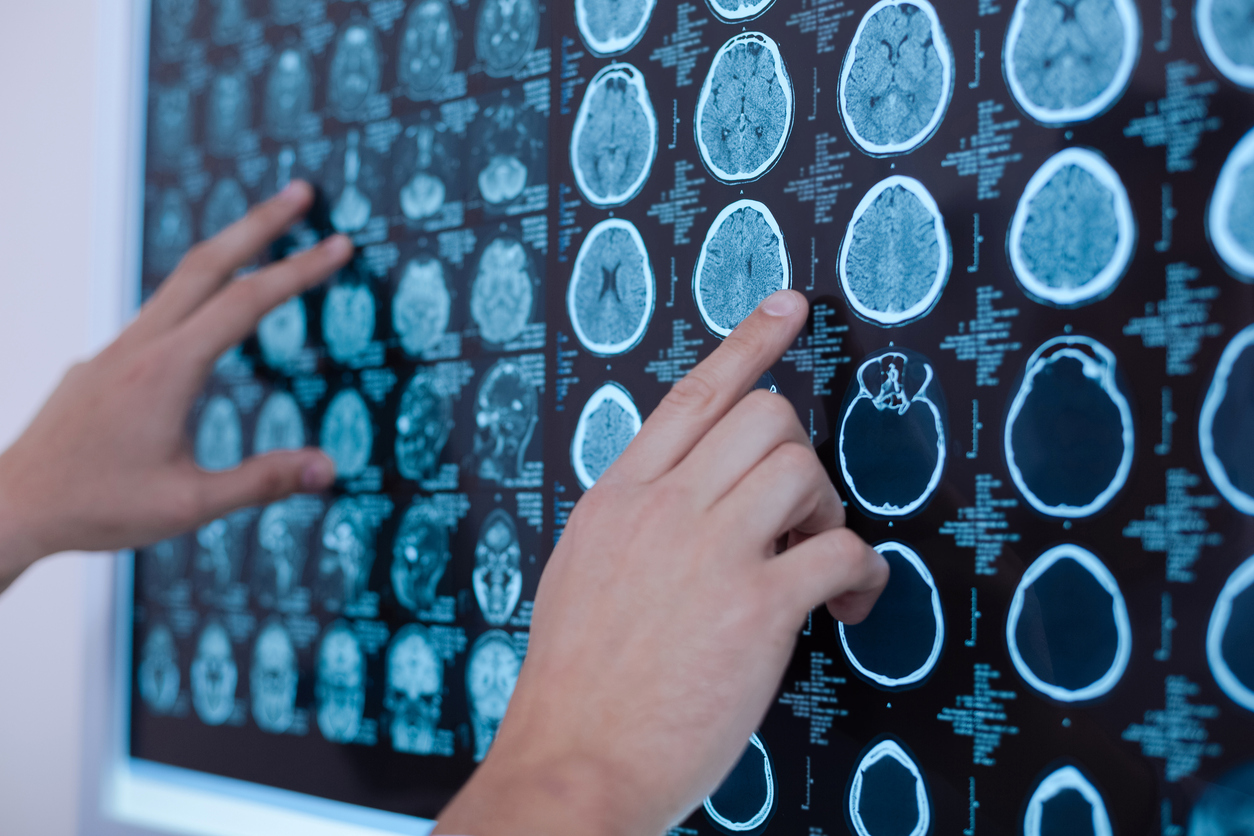

Dr. Sam Gandy of Mount Sinai hospital is trying to move beyond diagnosing CTE only in the dead, by using scans to test for the disease in the living. “It’s important to estimate prevalence, so that people can have some sense of what the risk is.” In the past year, 36 veterans and athletes have been tested for the disease at the clinic at Mount Sinai. A radioactive substance tracer is infused into the patients. The idea is that the tracer will cling to the dead clusters of protein, Tau, which is indicative of CTE. Pet scans are compared to MRI findings to identify the clumps of Tau. From this a diagnosis can be given, and hopefully more treatment options will be found. Until then, our job will be to continue treating the symptoms of the disease and attempt to delay additional complications through improving and maintaining functional performance through strength, balance, and cognitive training, as well as education.

Sara Strain, OTR/L, Director of Clinical Operations for Rehab Resources